Z Potentials | Baoping Wang, Alibaba’s Former Frontend Tech Lead and Yuque Founder, Resigns from ByteDance Exec Role to Launch AI-Powered Content Creation Tool, Secures Nearly $10M in Seed Funding

Z Potentials invited Baoping Wang, founder of YouMind, to give a talk.

In this edition, we’re thrilled to feature YuBo (real name: Baoping Wang), a widely respected developer in the internet industry. From conducting optics research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences to leading front-end engineering at Alibaba, and now launching YouMind, his journey reflects a deep commitment to technology and innovation.

YuBo’s story begins in a remote mountainous region of Hunan. He started out studying physics at the University of Science and Technology of China and went on to pursue optical research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In his third year of graduate school, he made his first pivotal decision—dropping out to pursue a career in programming. Over 15 years at Alibaba, Bo not only honed his engineering skills but also built several major products, including Yuque.

In early 2024, Bo made his third major life decision: stepping down from an executive position at ByteDance to launch a startup. For him, the decision wasn’t about right or wrong—it was about waking up each day with energy and excitement.

YouMind’s vision is to become “the pen and paper of the AI era.” The company aims to redefine how people gather information and write through innovative AI-powered tools, creating an all-in-one platform for content creators. Looking ahead, YuBo hopes to expand YouMind from a personal productivity tool to a lightweight team collaboration platform—and eventually a full-fledged content community.

YuBo’s journey and the founding of YouMind are not just stories of technological breakthroughs and product building, but also of personal growth, values, and responsibility. He believes that in any era, what matters most is understanding users, pursuing genuine passion, and driving constant innovation. YouMind, as the “pen and paper” of our AI age, is his way of unlocking new creative possibilities.

Whether you’re launching a startup or driving innovation within a large company, it all comes down to finding gaps in the market—those overlooked spaces others tend to ignore.

In the long run, YouMind’s mission is to become the “pen and paper of the AI era.” Over the next 6 to 18 months, the focus is more defined: a writing and research tool tailored to creators working on medium- to long-form content.

When we talk about the AI era, I believe some fundamentals remain unchanged—like the need to truly understand users and their real-world scenarios. For creators of AI applications, it’s essential to take a product management approach similar to that of the internet era: focus on the user, understand their context, and keep a close feedback loop.

Because AI is full of uncertainties, product managers who don’t fully grasp the technology may easily get off track. They might overestimate what AI can do and end up building impressive-looking demos that have little real-world value.

My long-term vision for YouMind? Perhaps in ten years, it might grow into a new kind of YouTube for the AI age. We imagine a tool that starts as “pen and paper,” but the content you write could eventually become interactive and playable. A single “playable page” might evolve into a video, and a collection of those might form a next-generation YouTube.

Wherever you are in your career, whatever you’re doing, you should reflect on what you’re good at and what you truly enjoy. The two may not always align, but knowing even one of them is a good start. If you’re still unsure—just start doing something concrete. Don’t overthink it.

In my own path—from engineering to product to management—I’ve always known my strengths but didn’t always know what I loved. First, master what you’re good at. And if you’re lucky enough to discover what truly excites you—go for it. When you’re doing something you genuinely love, you don’t need to justify it. That unspoken joy is the proof. If you need to find reasons to convince yourself, then maybe it’s not real.

01 YuBo, Founding Engineer of Yuque and Former Frontend Lead at Alibaba: Three Pivotal Career Moves, from Dropping Out of a PhD Program to Founding an AI Startup

ZP: YuBo, thank you for joining us. To start, could you introduce yourself to our readers? Feel free to begin with your academic background and walk us through any key milestones or turning points along the way.

Baoping: Thank you for the invitation. My journey has been fairly straightforward. I was born in a remote mountainous area of Hunan province. I studied physics at the University of Science and Technology of China and was later admitted to a combined master’s-PhD program in optical physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. But I didn’t finish the program—I chose to drop out. That was the first major turning point in my life.

Why was it so pivotal? Because from that moment, I left the world of academic research behind and fully committed myself to writing code. During grad school, I spent a lot of time conducting physics experiments that generated large volumes of data. I had to process this data using C, and in the process, I gradually realized that my real passion wasn’t in physics—it was in programming. I would often sit in front of my computer for days on end, completely immersed in code, barely pausing for food or sleep.

I was lucky to have a supportive advisor at the Institute of Physics who recognized my interest in software development. He recommended me for a role at the Institute of Software, where I got my first job. There, in the Internet Lab, the professors treated me almost like a student, which gave me the time and space to study computer science systematically—both undergrad- and graduate-level material. I’m very grateful for that.

My second major decision came when I left the Institute of Software to join Taobao UED in Hangzhou, focusing on user experience. The first turning point was discovering my passion for code. The second was about realizing that while I enjoyed coding, I was even more excited about building products for real users. At the time, I had considered switching directly into product management, but I lacked experience—so I decided to start from what I knew best: writing code. At Taobao UED, I was lucky again. Right after joining, I was thrown into deep work: contributing to a massive rebuild of the Taobao platform. I worked heavily on its transaction systems, and for the first time, I felt the weight of how even a small change in code could affect millions of users. It taught me to respect code—and sparked the desire to one day create my own product.

I stayed at Alibaba and later Ant Group for about 15 years. Over the years, I wrote a lot of code, but I also spent four to five years leading product development on tools like Yuque, CloudNote, and SwiftNote. I eventually managed a team of over 600 people, which came with plenty of hard lessons in leadership and organizational design. After leaving Alipay, I joined ByteDance for a year to work on Feishu (Lark). I’m thankful for that experience—it gave me insight into how ByteDance differs from Alibaba, which proved very useful for my startup journey.

My third big decision came in early 2024 when I left the corporate world to start my own company.

Looking back on these three choices, I can clearly see what matters to me and what doesn’t. What matters most is whether the work I’m doing excites me—whether it genuinely sparks passion from within. When that passion fades, it’s time to move on. What doesn’t matter to me? Sunk costs, or what other people think. For instance, when I dropped out of grad school, many friends advised me to stick it out and get the degree. But once I knew my heart was in coding, even one more day in class felt like a burden. It was the same at ByteDance—once I knew I wanted to build something of my own, no salary or title could change my mind.

There’s no absolute right or wrong in these decisions. But life only gives us so much time. For me, the most important thing is to live each day with passion and a quiet thrill.

ZP: I’m sure many readers are curious about the story behind Yuque. Could you share how it came about and what was going through your mind at the time?

Baoping: Sure. Yuque’s origin and development can be broken into three stages. It started at Alipay, back when Ant Group’s CTO division was planning a new initiative: a financial cloud service—think of it as an Alibaba Cloud with built-in financial features. Since this was a tech-driven platform, it required tons of documentation: PRDs, system design docs, user manuals, and so on.

At first, we used the internal knowledge management tools available—mainly Confluence and Jira. But we quickly ran into all kinds of issues: versioning, integration problems with our codebase, and limitations around automatic document generation. So we built a documentation system specifically for the financial cloud project. That system became the prototype for what would later be Yuque.

Between 2016 and 2017, this tool gained rapid traction within Alipay, especially among engineers and product managers. It became clear that it wasn’t just useful for that one project—it fit naturally into everyone’s daily workflows. So it evolved from a niche internal tool into the company-wide documentation platform. In other words, Yuque was born out of a real need—a documentation and knowledge management system designed specifically for tech teams.

By 2018, we began to consider extending Yuque’s use beyond Ant Group to the larger Alibaba Group. It was quickly adopted within Alibaba as well, replacing the existing internal documentation systems. At that time, our daily active users (DAU) had already reached tens of thousands. Recognizing the momentum, we saw an opportunity to scale externally.

2018 was a pivotal year for the document space—Tencent Docs and DingTalk also entered the field. The entire industry was moving in this direction. From 2018 to around 2020, we pushed Yuque into the public sphere and experimented with commercialization. We positioned it as an enterprise-grade knowledge base system. Given its integration with the Alibaba and Ant ecosystem, many affiliated companies adopted it enthusiastically. For financial institutions already trusting Alipay’s security infrastructure, embracing Yuque as a documentation tool came naturally. Growth was solid.

From 2021 to 2023, we shifted our focus back to internal usage, while also exploring some B2C initiatives—such as developing Yuque’s mobile app. After 2022, we doubled down on B2B operations, focusing more on revenue. Our core user base remained centered on Alibaba and Ant Group, where Yuque served as the internal documentation platform, but we still had the capacity to push forward with commercial efforts. When I left, Yuque’s trajectory was firmly upward.

ZP: Looking back, what do you think was Yuque’s smartest decision?

Baoping: One thing stands out—we understood the true nature of “documents,” and in doing so, we intentionally moved away from them, choosing instead to focus on structured knowledge bases. At the time, Tencent Docs, DingTalk Docs, and various other players were all exploring the document space. Many assumed that collaborative documents would be the next big thing. But given our context, that direction didn’t make strategic sense. DingTalk, after all, had its own document product. And most roles outside of engineering and product management were still using Microsoft Office. Challenging those incumbents—either Office or DingTalk—simply wasn’t feasible, not in terms of resources or logic.

But when we dug deeper into user needs, we uncovered something different. Users didn’t just want to write isolated documents like a Word file and distribute it via email or DingTalk. A large portion of their needs centered around composing multiple interconnected documents with structure—what we came to call a knowledge base.

A knowledge base is, essentially, a system of organized documents. This was an area that DingTalk’s document tool struggled with—even their later efforts couldn’t quite get it right. One might even say that Feishu (Lark) failed to master the knowledge base space as well.

So in essence, Yuque carved out a niche in the structured knowledge base domain for enterprises, a space few others were exploring. Whether in a startup or a corporate innovation context, success often comes from identifying such “gaps”—those overlooked corners of the market. And in those unglamorous spaces, you often find the least resistance.

ZP: How far did Yuque eventually grow?

Baoping: Yuque operates in two tracks. One is a self-hosted, internal deployment used across Alibaba—at its peak, over 80% of employees were active users. Usage remains high to this day. The second is the public-facing version at yuque.com. While enterprise user numbers may have fluctuated, by the time I left, we had launched over ten thousand corporate “Yuque spaces,” and monthly active users had peaked at over ten million.

ZP: Could you share the thinking behind your recent decision to start your own company?

Baoping: The idea of starting something new had been on my mind since 2019. But then the pandemic hit, and the team was going through a rough patch, so I chose to stay. Suddenly, four years passed in a blink—and that terrified me. You only get so many four-year stretches in a lifetime. I imagined staying at a big company. Alibaba treats its employees well, and I could’ve continued managing a sizeable business unit. But it didn’t feel like the life I wanted.

What do I want, truly? What brings me joy? That question haunted me. In my final years at the company, I slowly found my answer: what excites me most is building products that serve people. Of all the work I did on Yuque and Feishu, the moments I loved most were talking to users. For example, I never imagined that physical telecom stores could use Yuque to train new staff—but they did. It was the same with Feishu: tools like these reshape productivity and collaboration.

To create a tool that empowers millions—that, to me, is a source of endless excitement and meaning.

02 YouMind: The Paper and Pen of the AI Era — A Unified Tool for Multimodal Content Creation and Project Management

ZP: Let’s start with a quick introduction to YouMind. What does the product do, and who is it built for?

Baoping: YouMind’s positioning can be understood in two phases: its long-term vision and its current focus.

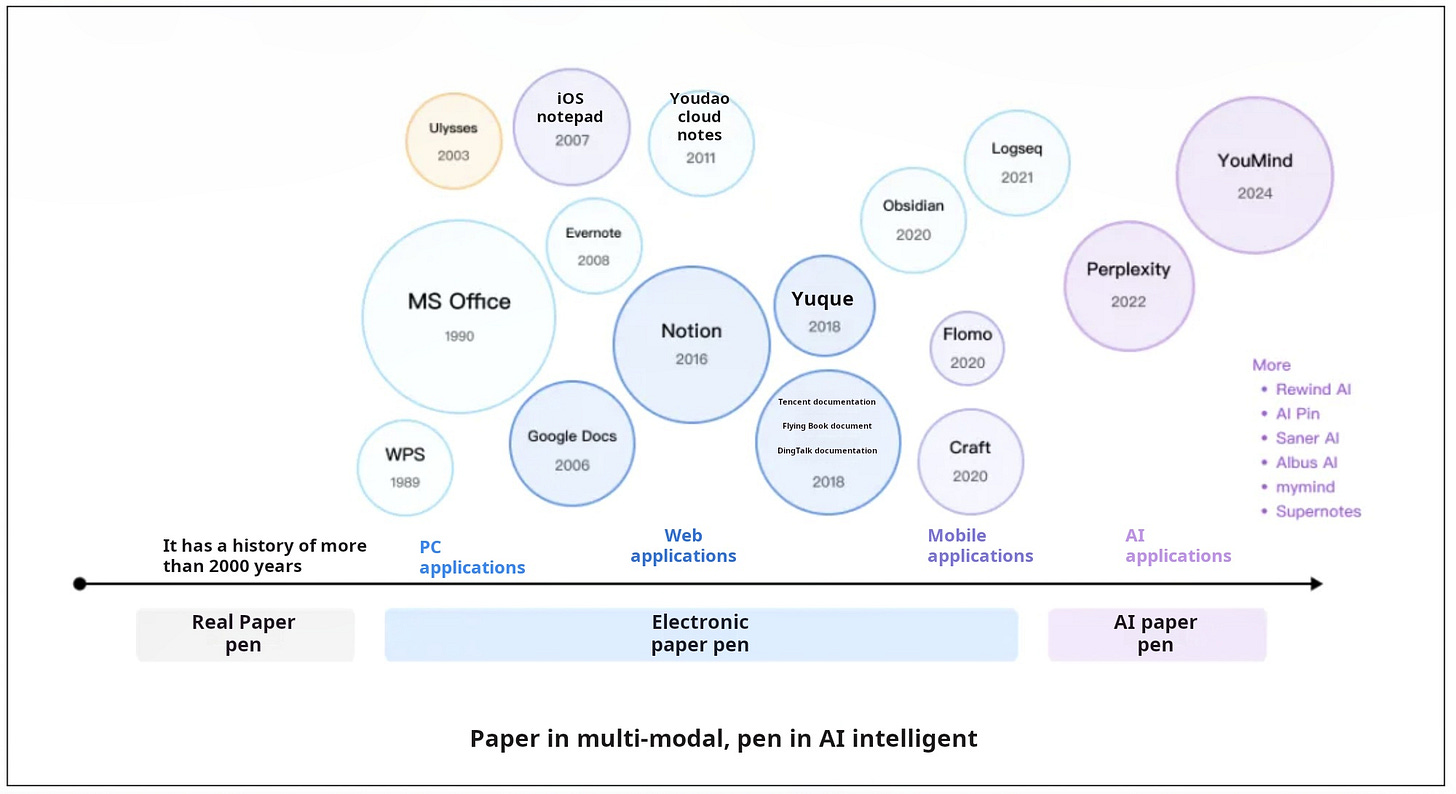

In the long term, YouMind aspires to become the “paper and pen of the AI age”—or, if you will, Paper & Pen 3.0. The 1.0 version was traditional writing tools—ink and parchment, enduring across millennia. The 2.0 version brought digital documents and note-taking software like Office and Notion. Now, with AI and the rise of multimodal media, we see an opportunity for a 3.0 evolution—a new generation of tools that blends artificial intelligence with multimodal content. That’s the vision we’re pursuing.

Of course, that can sound a bit abstract. So let’s zoom in on our short-term focus. Over the next 6 to 18 months, YouMind is designed as a productivity tool for creators of medium-to-long-form content, helping them research and write. That includes long-form articles, podcast scripts, or videos longer than three minutes—any creation that begins with ideation, research, and drafting before moving on to recording or AI-generated production. In the near term, YouMind is here to streamline that early-stage creative work.

ZP: Do content creators have different needs when it comes to short-form versus long-form tools?

Baoping: Definitely. In talking with users, I’ve found that creators working on longer content need entirely different tools from those working on quick-turnaround content. The creator economy is diverse—spanning text, podcasts, video, and short-form clips—and each format comes with its own demands. Length is another dividing line: most content on short-video platforms like TikTok or Douyin is under 2.5 minutes and optimized for fast consumption.

Short-form content tends to prioritize speed and ease of use. Often, the platform itself is the creation tool—think of apps like Jianying (CapCut) or platforms like Weibo.

In contrast, we’re initially focused on users who need to write. These users are producing content like newsletters or WeChat articles. As we move forward, we’ll also serve podcasters and knowledge-based short-video creators, who typically draft outlines and collect materials beforehand. For them, writing is still a core step—even if the final output is audio or video.

ZP: Before we dive into product specifics, how would you describe the industry YouMind operates in? What does the landscape look like?

Baoping: YouMind sits within the broader category of content creation tools, a large and rapidly evolving space. Multimodal content consumption is a growing trend, and behind it lies a simple truth: content creation tools are still fragmented. Some companies focus on video generation, others on audio. There are legacy players in text and note-taking. That’s the media axis. But YouMind structures the creative process differently by phases of creation and production.

Most creative work moves through five stages: topic selection, research, writing, production, and distribution. While that sounds linear, in reality the process is messy and overlapping. Sometimes you’re doing three at once.

Lately, I’ve been experimenting with content on Xiaohongshu and podcasting, and the process has confirmed this. Content creation isn’t a sequence; it’s a tangle of five interlinked modules, each surfacing unpredictably.

Across all formats, I’ve seen the same bottlenecks: researching and drafting. These steps are still underserved.

Most people still rely on conventional search engines—or, at best, use ChatGPT. Then they open dozens of browser tabs, clustering them by topic. It’s not an elegant experience. As for writing, even with AI tools around, many creators still fall back on Notes, WPS, or Office. That’s why we believe there’s room to reinvent how people research and write in the age of AI and multimodal content. That’s where YouMind comes in.

ZP: What are the main technical challenges in making YouMind a successful product?

Baoping: The core technical difficulty lies in waiting for the foundational models to grow stronger. For example, many tools are trying to build summary functions, but there’s often a mismatch between what product managers assume and what users actually want. Users often use summaries to filter content rather than to quickly read it, which runs counter to the designers’ original assumptions. In reality, the needs for summaries vary depending on the context.

Today’s foundational models—Gemini 2.0, GPT-4o, OpenAI’s o1, and others—are already quite powerful. But when it comes to sourcing information, users often come with clear intentions and hope AI can help them extract relevant details from massive troves of content. The problem is, doing that well still requires a lot from the user.

Take, for instance, products like Notebook LM, where users can upload PDFs, web pages, and other materials, then write a prompt telling the AI what they want to extract. If users are skilled at crafting prompts, they can make it work. At present, foundational models can achieve a 60% to 70% success rate, which is decent. But here’s the crux: the information users seek is often highly personal and nuanced, and current AI still struggles to interpret and fulfill those individual needs.

Let me give you an example. One user loves reading illustrated articles, especially those with personal anecdotes. He wanted an AI tool that could sift through vast content and extract these authentic stories, preserving the original tone and formatting. That seems like a reasonable ask, doesn’t it? But in practice—even with GPT-4o or similar models—it takes multiple rounds of dialogue for the AI to even begin to grasp what he really wants.

Over the past year, we’ve seen great strides in multimodal understanding—especially the ability to move from multimodal inputs to outputs. But foundational models still need time to mature. For example, I’d love for AI to help me draw simple illustrations. Claude 3.5, through its Artifacts feature, can now use SVG to render vector graphics. It can sketch shapes. But to truly draw what’s in my mind—a mental map, say—that remains extremely difficult.

ZP: How competitive is YouMind’s niche within the broader industry?

Baoping: I’ve been observing this field for two or three years now, and the best phrase I can find to describe it is: “A hundred flowers bloom, a thousand corpses lie.” That is to say, the field is crowded, both domestically and internationally.

This wave of products is, in some ways, inspired by Figma—a truly outstanding tool. Figma offers flexible layout design, whiteboarding, and now integrates AI into sourcing and writing. A great variety of products are blooming, yes, but I don’t believe any of them have yet found PMF (Product-Market Fit). Everyone’s still on the way, groping through fog—including myself. When we first started building YouMind, we asked whether the free-form canvas structure, à la Figma, might be a good carrier for our writing tools. We even prototyped it. But after spending a few months testing it with real users, we discovered the workflow just wasn’t effective.

When you think deeply about the nature of writing, you realize these product forms can actually clash with the process itself. These free-form tools do a good job helping users gather information because that’s a divergent process. But writing is something else—it’s convergent. It requires the writer to extract a tree structure from a vast web of content, and then render it in a linear form. It’s a process that narrows and sharpens, from web to tree to line. Free-form canvases encourage divergence, not convergence. They are ill-suited for writing.

So, for the drafting phase in YouMind, we realized the free-form canvas was not the right form. We’re now exploring new paradigms. This is a space that demands continuous innovation and reinvention.

ZP: What makes YouMind’s positioning unique within the industry?

Baoping: Our differentiation lies in this pairing: sourcing and drafting. That’s a distinct combination. There are plenty of tools focused on sourcing—especially PKM (Personal Knowledge Management) platforms. But I believe making yet another PKM tool has little meaning; it won’t create differentiated value. There are also many drafting tools. But writing is rarely the start of the process. Most users just want to get something done. So I ask: is there a way to merge sourcing and writing? To make 1 + 1 > 2? That might be a true point of difference. I think convenience can be transformative. Xie Xin, the CEO of Feishu, once said, “Convenience equals effectiveness.” And often, convenience stems from All-in-One design.

Our second differentiation is something I’ve only recently begun to articulate. YouMind is not, at heart, about knowledge management. It’s about project management. That’s a major divergence from the market. Many content creators don’t operate from a base of long-term accumulation—they act when inspiration strikes. A fleeting thought, a sudden resolution—say, “I’ll post weekly from now on”—triggers a flurry of activity: topic selection, information gathering, and drafting. This is not a knowledge pipeline; it’s a project workflow. YouMind is still in internal testing. We’re focused on improving the information-gathering stage, while the drafting stage is undergoing product refinement. Our hope is to craft a truly distinctive product experience.

03 Beta Users’ Conversion Rate Far Surpasses Expectations; First Round Raises Nearly $10 Million; Plans to Build a Content Creator Community

ZP: What’s the One Metric That Matters(OMTM) your team is currently most focused on? How is it performing?

Baoping: At the moment, we’re tracking two main metrics. The first is retention. Specifically, I place the most importance on 7-day retention. For instance, if 100 users sign up today, how many are still around after seven days? For AI applications, achieving a 20% retention rate is quite difficult. Our current goal is 15%.

The second metric is a simpler one: the conversion rate of our beta users into paying customers. This has somewhat exceeded our expectations. In the internet era, a B2C tool with a conversion rate of 1–3% is considered quite good. For YouMind, the initial beta data has already exceeded 3%.

ZP: What are your plans for the product and company over the next few years? What’s the goal you most hope to achieve?

Baoping: Recently, I’ve been working on planning for 2025 and beyond, though to be honest, things still feel a bit hazy—early-stage startups tend to think in three-month windows. Our immediate goal is to shape YouMind into a tool for “super-individuals,” using AI to deliver a seamless experience for both research and writing. That’s the three-to-six-month horizon.

A year or two from now, we might move into small team collaboration tools. We’ve noticed that whether for solo creators or international peers, the SMB market is crucial. I’d like to address the transition from single-user to multi-user collaboration—but always rooted in the core features of research and writing. That’s the second phase.

Longer-term, we hope to build a home—or a small community—for content creators. That’s a more ambitious goal, but one that excites me. We might focus specifically on serving content creators, creating a kind of GitHub or Reddit—but for the creator economy.

ZP: Besides building a great product, what else do you consider essential?

Baoping: I think what’s most important depends on the stage we’re in. In the first stage, I like to borrow Jack Ma’s summary: find the people, find the money, find the direction. We’ve essentially completed our first round of financing, and made some initial progress on team-building. We’re still looking for distinctive talent, though—especially people who can drive global growth and operations. As for finding the direction, that’s about product and business strategy. I believe we’ve finished laying the groundwork of stage one and are now moving into stage two.

In this second phase, I think the key is marrying product and operations—especially user operations or “seed user” engagement, as well as continuous product innovation. Since October, I’ve poured much of my time and energy into the product—thinking hard about how to find true innovation points in a fiercely competitive, ever-changing industry, and sweating over the details of product design.

This process is both tedious and oddly fun. User operations are indispensable, because true product innovation depends on close communication with users. I believe it’s crucial to establish strong bonds with early users and involve them directly in shaping the product. At the moment, in addition to one-on-one interactions, we’ll soon begin operations on platforms like Jike and Xiaohongshu, and after the Lunar New Year, we’ll expand internationally. But the core purpose isn’t growth—it’s to find seed users: those “angel users” who will grow alongside the product and offer meaningful feedback.

As for stage three, I don’t have a clear idea yet—we’re still firmly in the second stage.

ZP: We heard YouMind just closed a new round of funding—congratulations! Could you share a bit about it?

Baoping: We completed our first round back in September. Grateful to the reputable investors who joined us—we raised close to $10 million.

ZP: You’re a well-known product manager from the internet era. How does building products in the AI era differ from those earlier times?

Baoping: I wouldn’t call myself a “well-known” product manager. But speaking of the AI era, I think some fundamentals haven’t changed—most importantly, understanding users and their real-world scenarios. That principle has held steady. Ironically, some practices that were once fashionable now strike me as outdated. For example, some incubators still stress that founders or founding teams should read AI research papers. I think this can be misleading. The ones who truly need to read papers are those working on AGI itself—if they don’t, they probably shouldn’t be in AGI. But for application developers? I find this insistence a little odd. There was a time when I, too, got anxious—consuming tons of news and chasing papers.

But in the process, I discovered a problem: this approach felt distant from users. I believe that for creators of AI applications, more energy should be devoted—just as in the traditional Internet era—to focusing on users: understanding scenarios, engaging in dialogue. This, in my view, holds far more value than reading countless research papers. A handful of foundational AI papers is quite enough.

What is different now, though, is that reading some papers—or rather, what Dr. Kai-Fu Lee refers to as the need for a Technology-Market Fit (TMF) in addition to Product-Market Fit (PMF)—is indeed necessary. The AI field is rife with uncertainty. When a product manager looks solely from the user’s perspective, without understanding the fundamentals of AI, it’s easy to veer off course. One might mistakenly believe AI can do too many things and create dazzling demos that, in the end, are of little actual value. In such cases, being grounded becomes crucial. You must use AI products yourself, firsthand, to understand where the real ceilings lie.

In this era, I believe it’s essential for product managers to stay grounded. And this groundedness can only be cultivated through one’s own efforts—by coding with AI, by reading accessible scientific papers, and by doing real research. In the traditional Internet age, product managers could afford to ignore these things; not anymore.

ZP: You’ve been running a startup for over half a year now. What’s the biggest difference compared to working at a major tech company?

Baoping: The main difference? Everyone’s busy—but the nature of the busyness is entirely different.

At big companies, I was often extremely busy for long stretches. But a lot of that busyness was aimless. There were endless meetings—ones you couldn’t refuse—and a constant stream of tasks. Especially once I moved into management, I was buried in trivial matters. At year-end, for example, you’d begin planning for the following year. Before the planning, you’d need pre-meetings just to decide who should attend the planning meeting. Your own team would also need to make a plan. Do you hold your own pre-meeting? It’s all layers upon layers of logistics. That kind of busyness, oddly enough, often felt more overwhelming than what I’m experiencing as a founder.

After starting my own venture, I felt a different kind of busy—a kind that’s purposeful.

Between May and September, I had to meet with investors, handle overseas company structure, ensure payroll was set up, manage reimbursements—even take care of office logistics, like who’s responsible for cleaning, who calls for more water when we run out. It’s messy, yes, but each task has a clear purpose.

Take the example of arranging office cleaning: once it’s settled, it’s done. This kind of busyness is focused. At a big company, it’s frantic and fruitless. But in a startup, it’s busy—but not wasted. Every effort pushes things forward or crosses an item off the list. That’s the difference. Whether it’s logistics or launching the browser plugin—something that once caused us anxiety—we now see users using version 0.1 and confirming that many of our early decisions were right. That gives us confidence: we weren’t just spinning our wheels.

04 “If You’re Lucky Enough to Figure Out What You Truly Love—Go Do It”; Aim to Build YouMind as the "YouTube of the AI Era"

ZP: You’ve played many roles in your career: engineer, product manager, tech executive, founder. What advice would you offer readers when it comes to making career choices?

Baoping: The first thing I’d say is this: No matter what stage of your career you’re in, no matter what you’re doing—keep thinking about what you’re good at and what you love. The two aren’t always the same. But even figuring out one of them is good. I ask myself this question every six months. Since starting a company, the rhythm has changed—it’s more like every year or two. This is assuming you care about your path. And if you can’t figure it out right away? Then go do something concrete. Don’t overthink it.

Looking back at my own journey—did I truly love front-end development?Honestly, from day one, I suspected I didn’t. I was good at it, but not sure I loved it. Still, I knew I was skilled, and since I didn’t yet know what I did love, I focused on doing what I was good at. Later, I worked on Yuque and became something of a product manager. In 2017 and 2018, I started catching up on all the product knowledge I lacked—reading books, studying frameworks, practicing what I learned.

Then came management. After 2018, I spent at least half my energy on managing teams. I read widely—psychology, leadership, anything relevant. I figured: if I’m going to do this, I should do it well. So from tech to product to management, my method remained the same: start with what I’m good at, even if I’m not yet sure I love it.

But here’s the last thing I want to say: If you’re lucky enough to know what you love—then go do it, without delay. For me, that “without delay” still took a few years, out of inertia. But even back in 2019, I already had a feeling: I loved building tools for content creators, tools for productivity. That’s what I wanted to do. That’s what I’m doing now.

What is the definition of interest? It’s when you do something and feel a kind of joy that needs no explanation—that inexplicable delight is what we call liking. If you still need to justify it, then I think it’s not real.

ZP: How did the YouMind team come together? Are there still talent gaps you’re looking to fill?

Baoping: The team actually began to take shape around last November, when I was still at Feishu and already planning to leave and start something new. Due to various circumstances, I didn’t officially leave until May. From then on, I began looking for talent. More than half of our current team members are old colleagues from Alibaba, including people who once worked with me. That’s one part. The other part consists of new hires from open recruitment. Right now, our team is still quite small. It’s me, three product designers, and eight product engineers.

I personally handle recruiting, fundraising, direction-setting, and various miscellaneous tasks. As for the three product designers—well, I believe they are neither traditional product managers nor designers, but something new: product designers. We’ve redefined this role. They not only write product requirement documents (PRDs), but also design the product itself, including interaction design and even some illustrations. They participate from the very conception of a product idea all the way through to high-fidelity prototyping. In the AI era, they must also consider what’s technically possible with AI. Fortunately, we’ve found three who truly fit this new AI-era definition.

Our eight product engineers form the backbone of the team. Some specialize in frontend, others in backend, and a few in iOS development. Each of them has their main technical domain, but they’re also quite versatile—for instance, a backend developer can still build pages, and a frontend developer can handle databases. We call them “product engineers” because we want them to do more than just code; we want them to influence the product itself, to reverse-inform product decisions through their implementation. We’ve had many cases where a design from the PM looked great on paper, but proved unworkable in practice—so we adjusted quickly.

We want engineers to be involved as early as possible in the product design stage. So the team is now roughly in place and up and running. But looking ahead, since we aim to become the “pen and paper” of the AI era, we are still understaffed.

There are three main types of talent we’re looking for:

First, what I call AI enthusiasts—people who are deeply engaged in AI practice. Our team members, myself included, already use AI extensively, but honestly, I don’t think it’s enough. We’re eager to find those who are already using AI to create, maybe even have product ideas of their own—people who can serve as fountains of inspiration. We welcome them either as full-time teammates or as advisors.

Second, we’re seeking talents in global growth and operations. From day one, we’ve targeted a global audience. Before the Spring Festival, we ran a domestic closed beta. After the holiday, we shifted directly to overseas operations. A few of us product managers are already hands-on with this, but we’d love to find others with more experience—ideally, folks who are passionate about our vision. We’re confident in our ability to figure things out, but if someone who’s been down this road could join us, it would make all the difference.

Third, we’re still short of certain types of engineers—particularly in product engineering. We need people who are experienced and passionate about editor technologies, and we’re also actively looking for iOS developers who not only have strong technical skills but a good design sensibility as well.

ZP: What are your hopes for YouMind and yourself in ten years?

Baoping: For YouMind, I hope that in ten years, we might become the YouTube of the new era. That’s actually where the name comes from—we borrowed the naming inspiration from YouTube. Some might say we’re building the “TikTok of AI,” but that’s open to interpretation. For me, it’s more like an AI-age YouTube. YouTube is filled with medium- and long-form content. Many of its users are learners, personal growth seekers. I believe AI is changing how videos are created and consumed. What we want to build is the paper and pen of the AI age—something that, once written, can move and play. Imagine a playable page—that’s our idea of a new form of video. And a collection of such playable pages could be the new YouTube.

This vision is quite distant—maybe ten, maybe even thirty years out. But I hold onto it. As for myself, I haven’t really thought about where I’ll be in ten years. What matters more to me is getting things done—seeing things through. What I truly hope for is to find kindred spirits who share this vision and want to go far together. If I can be one of them and do my part, I’d be content.

ZP: The past year or two has been a whirlwind for the AI industry. What’s the one event or person that left the deepest impression on you?

Baoping: Without question, the release of ChatGPT. It was a true moment of revelation—like seeing the curtain rise in a new era. It marked the arrival of the AI age.

As for a person, I’d say Ilya Sutskever stands out the most. What struck me wasn’t just his technical prowess, but his almost philosophical reflections—like “compression is intelligence.” His insights into the Transformer architecture and neural networks felt like deconstructing intelligence itself. I studied the sciences myself, so I’ve always had an interest in these questions: What is reasoning? What does it mean for a machine to think?

In the early days of AI, the symbolic school saw reasoning as a logical process—a system of equations, a formal language. But Ilya’s interpretation showed me how neural networks, by learning to predict, are in essence already performing reasoning. His ideas offered me a new lens—one that blends neuroscience, cognitive science, and AI into a shared inquiry. It felt like he was peeling back the veil to reveal an entirely new world.

ZP: What’s the most interesting AI product you’ve seen recently?

Baoping: Devin. Our company pays $500 a month for it.

Back in the world of programming, the rise of AI coding tools feels like the shift from manual to automatic transmission in cars. Not long ago, there was another popular tool called Cursor. The way I see it, traditional IDEs are like stick shifts—manual, hands-on. Cursor, in contrast, is automatic: it accelerates development, especially in areas where you lack deep expertise. It completes code rapidly and intuitively.

Now, if you think of software development like autonomous driving, there are levels, L1 to L4. Devin isn’t fully autonomous yet; I’d place it at L3. You can think of it as a coding intern—helpful, but still in need of oversight.

Using Devin, you submit a request in a chatbox or upload a screenshot of a backend admin page. Devin digests the context, writes the code, pauses for confirmation if it’s uncertain, then proceeds. Within 30 minutes to an hour, the code is ready to merge and deploy. Right now, it’s at an intern’s level—not dazzling, but it has something irresistible. Despite its slowness, it’s deeply appealing. Even someone with limited coding experience can achieve results, so long as their needs are clearly expressed.

Cursor is like an automatic car—you still steer, you still drive. But Devin begins to imagine for you, and that’s a different proposition altogether.

ZP: Any books or articles you’d recommend to our readers?

Baoping: The Joy of Confucius by Taiwanese writer Xue Renming Xue. It’s a personal interpretation of Confucius and Mencius, but really, it delves into the essence of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism within traditional Chinese culture.

What makes this book rare is its gentle tone. It doesn’t provoke anxiety; instead, it seeks to revive the grace and bearing of Confucius’ thought—whether in Taiwan or mainland China. I found it especially resonant because it aligns with YouMind’s philosophy. In my view, YouMind is not the next TikTok of the AI age. I actually dislike that comparison—TikTok, in this era, already exhausts people and spreads anxiety. If AI made TikTok even more efficient, I fear society would grow only more overwhelmed.

Instead, I look to culture and language to shape new modes of consumption. In my mind, the next-generation “YouTube” isn’t driven by short videos. Trends may push us that way, but not all trends are worth following. Some things that seem viral are simply transitory—they mesmerize, but they don’t endure.

The Joy of Confucius is a work steeped in the ancient cadence of Chinese tradition. Perhaps in our frantic, fast-paced world, this antiquity—this quietude—offers an answer.

Disclaimer

Please note that the content of this interview has been edited and approved by Baoping Wang. It reflects the personal views of the interviewee. We encourage readers to engage by leaving comments and sharing their thoughts on this interview. For more information about YouMind, please explore the official website: https://youmind.ai/.

Z Potentials will continue to feature interviews with entrepreneurs in fields such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and globalization. We warmly invite those of you who are hopeful for the future to join our community to share, learn, and grow with us.

Image source: YouMind & Baoping Wang